The Problem With Calling the U.S. an Outlier on Vaccines

And why a little-known commission, a severe flu season, and a hepatitis B vaccine study in Africa deserve attention

Last week, MedPage Today published a piece I wrote titled “Parents Are Confused. I’m Worried for My Pediatric Patients.” I wrote it after a recent series of conversations in clinic that felt meaningfully different from the questions I usually hear about vaccines.

These conversations weren’t driven by misinformation. The parents were disoriented.

One parent summed it up well with this question: “What vaccines are recommended now? I’m so confused.”

I’ve heard some version of that question several times this week, including from families who previously made confident, routine decisions to vaccinate.

That confusion is the predictable outcome of an overnight rewriting of the U.S. childhood vaccine schedule, justified as an effort to “restore” or “rebuild” trust.

This rationale deserves far more scrutiny than it has received.

The argument appears to go like this: the United States is a negative “outlier” compared to peer nations; routine childhood vaccination is facing a crisis of trust; and recommending fewer routine vaccines will lead parents to trust clinicians more.

As someone who studies vaccine delivery and communication, and who sits with families every day, I can say plainly: each of those assumptions is backwards.

This week, I want to examine the assumption underlying all of them: that the U.S. being an outlier in childhood vaccination is inherently a problem.

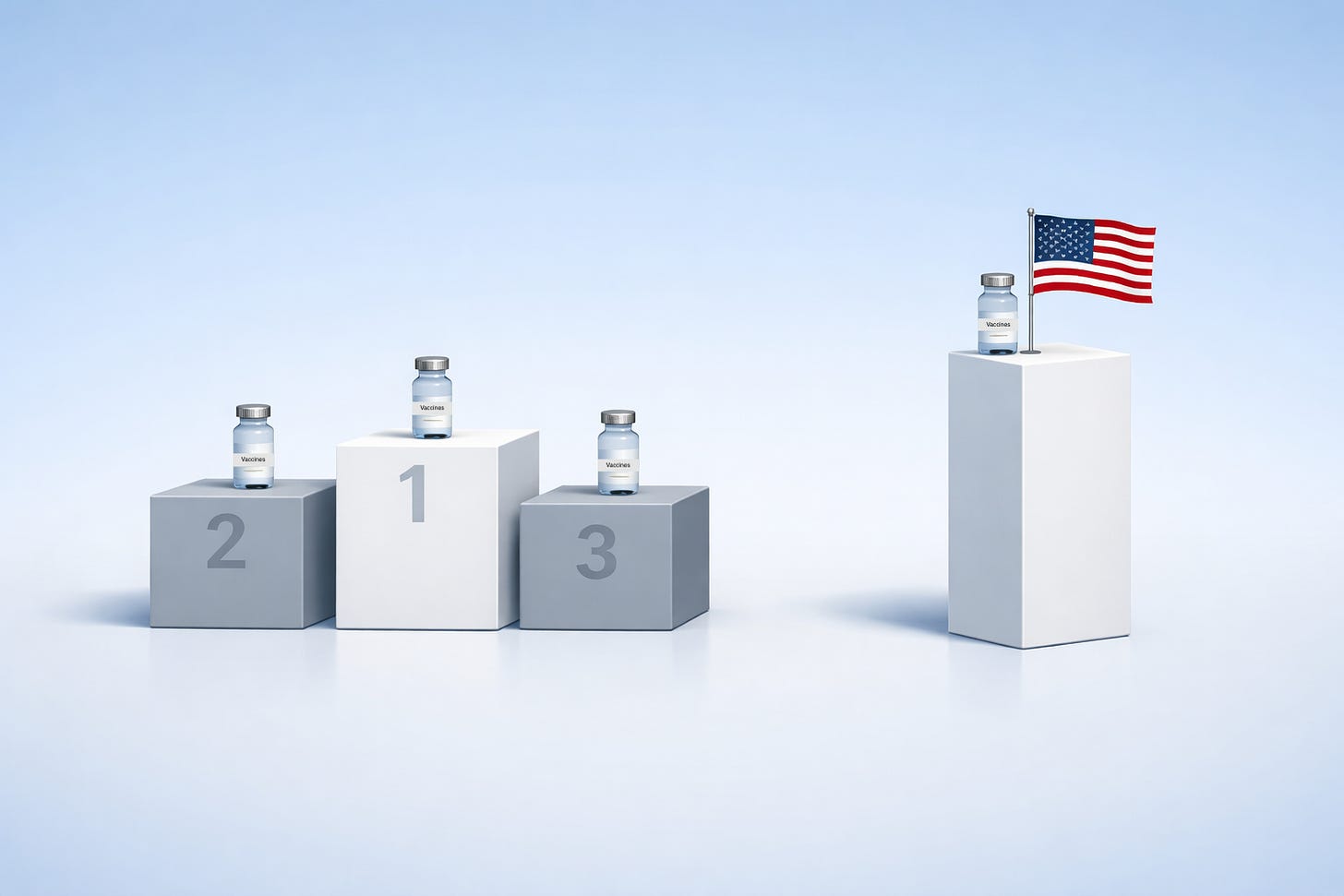

Almost no one is framing the possibility that the U.S. is an outlier because it was a leader in preventing childhood disease.

Is Being an “Outlier” a Problem?

One of the most common justifications for the schedule overhaul is that the U.S. was an “outlier” compared to peer nations, often citing countries like Denmark.

Many responses have focused on whether that claim is even accurate, noting correctly that the U.S. schedule is not dramatically different from those of many peer countries and that Denmark is itself an outlier.

While these points matter, they skip over the more revealing assumption embedded in the argument: being an outlier is evidence of a problem.

Being ahead of peer nations in preventing life-threatening disease, using one of humanity’s greatest achievements, is only a liability if you assume routine vaccination is a problem and we should do less of it. That conclusion is being treated as self-evident without ever being defended.

The U.S. has been an outlier in plenty of other domains where “different from peers” is rarely invoked as a warning sign. We have been an outlier in landing humans on the moon, building the internet, and sequencing the human genome. In none of these cases is outlier status taken as evidence that we should pull back to align with peer nations.

Difference, on its own, tells us nothing about whether a policy is good or bad. What matters is evidence of harm, risk, or unintended consequences that outweigh the benefits.

And this is where the justification falls apart.

We’ve been offered no new evidence that broader protection against vaccine-preventable diseases has become a liability rather than a strength. Instead, the vaccine schedule is being rewritten as if that conclusion were already established.

I joined the ScienceVs podcast this week to talk through these issues, and one point I tried to make there was this:

The fact that we have vaccine coverage for more diseases is not evidence of a problem. That's backward. It's not a competition to see how few diseases we can prevent.

Why “Peer Nation” Comparisons Fall Short

Setting aside the unexamined assumption that more vaccines are inherently problematic, the fact that another high-income country does not routinely recommend vaccines reflects different policy trade-offs, not a lack of evidence.

Vaccine schedules are shaped by national context, including disease epidemiology, health-system capacity, financing, equity, and the reliability of follow-up care. Those factors matter enormously.

Denmark has a smaller population, far less inequality, and universal health coverage. In that setting, policymakers can reasonably assume timely access to care, consistent follow-up, and fewer structural barriers. The U.S. operates under very different conditions.

Here, the childhood vaccine schedule must compensate for gaps in access, delayed diagnosis, inconsistent follow-up, and wide variation in healthcare delivery. It functions, in part, as a proactive clinical safety net, one designed to protect children despite those system-level weaknesses.

That difference is often overlooked.

I recently spoke with a pediatrician who practiced for many years in Denmark before moving to the U.S. He had many positive things to say about the Danish healthcare system, much of which we should aspire to replicate. Yet he viewed Denmark’s more limited vaccine schedule as a weakness, not a strength, particularly given how well the U.S. program has prevented disease across a far more complex system.

Calling the U.S. schedule an “outlier” was never evidence that it was wrong. In many cases, it meant we were setting the pace.

In fact, peer nations often move toward the U.S. over time. The United Kingdom’s recent adoption of routine varicella (aka chickenpox) vaccination is one example. And even Denmark recently added the RSV vaccine during pregnancy, following the U.S. lead.

Here’s the irony that isn’t being widely acknowledged: The U.S. is now becoming an outlier in the opposite direction, and we are narrowing protections while other countries expand them.

I’ve written more about how these country comparisons are misleading with Unbiased Science here:

A Few More Things That Deserve Attention This Week

Another Development Is Unfolding Quietly, With Big Implications

While most attention has focused on the overhaul of the childhood vaccine schedule, something else is happening that has received almost no scrutiny.

As of today, The Hill has confirmed that at least 4 members of the Advisory Commission on Childhood Vaccines (ACCV) have been removed. This obscure commission advises HHS on the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), the no-fault system Congress created to compensate rare vaccine injuries while protecting vaccine access and supply.

This matters because the ACCV sits at the legal and financial foundation of the U.S. vaccine system. It has also long been a target of anti-vaccine activists.

The commission advises the Secretary of HHS on what counts as a vaccine injury, which injuries are presumptively compensable, and how the Vaccine Injury Table is updated. Those decisions shape liability, compensation, and ultimately whether vaccines remain viable to produce and offer at scale.

Changes to the ACCV rarely draw headlines. But the replacement of members can profoundly alter how changes to the vaccine injury system are justified and whether the balance Congress struck in 1986 continues to hold.

Some reforms could meaningfully improve the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. But, if responsible reform is truly the goal, these removals are difficult to square with that claim.

One of the members who was removed is a close colleague. I can say without hesitation that they are one of the most thoughtful, compassionate, and principled pediatricians I know. They bring care, balance, and seriousness to difficult questions, and if the aim is meaningful, good-faith reform of the VICP, they are precisely the kind of person you would want at the table.

These are precisely the kinds of procedural moves that can reshape a system before most people realize it is happening. And the risks to vaccine access and to families’ ability to choose vaccination in the U.S. are real.

I wrote more about these risks with the ACCV and VICP last month with colleagues from Unbiased Science and Your Local Epidemiologist here:

Influenza Update

One final note on influenza.

This has been a particularly severe flu season. While local data in Colorado suggest we may be past the most recent peak, substantial influenza is still circulating in the community, and I continue to see it regularly in my patients.

Two points are especially important to emphasize.

First, it is not too late to get vaccinated. Earlier vaccination is ideal, but protection still matters now. The best time to get a flu vaccine was earlier in the season; the second-best time is today.

Second, the vaccine works. Early laboratory data sparked rumors that this year’s flu vaccine is ineffective against the predominant circulating strain, H3N2 subclade K. Those claims may have been overstated. While no flu vaccine is perfect, and effectiveness estimates are often not clear until well after the season ends, the available evidence shows the vaccine produces antibodies that recognize this circulating strain and provide meaningful protection, especially against severe disease.

Finally, as I said to NPR this week, weakening influenza vaccine recommendations in the middle of a severe flu season is irresponsible and dangerous. I continue to recommend influenza vaccination for all my patients.

Thanks, as always, for being part of this community.

-David

Do you like this newsletter?

Community Immunity is free for everyone. If you find it valuable, please subscribe below and help spread the word!

You can also follow me on LinkedIn, Instagram, Substack Notes, and Bluesky.

Powerful framing about the US being a leader rather than an outlier. The point about Denmark's healthcare context vs US gaps in acess totally shifts the conversation away from simple country comparisons. Had a patient last week who couldn't afford a followup appointment, which made me realize how much preventive care has to do the heavy lifting here. The Guinea-Bissau hepatitis B study cancelation is wild, like we've learned nothing from past ethical failures in global health research.

Yes, US was an outlier - a leader, as you make so clear.' Thanks! I mourn the loss of US leadership in immunization and vaccine science that has been so helpful in my working in immunisation in nz and globally. I pray that that it will not be entirely lost, and that the US will come back; to sanity.