"Do You Believe in Science?" The Question That Divides Us

To restore trust, we must stop dividing people into believers and deniers.

Hi,

I’m Dr. David Higgins—a pediatrician, public health physician, and researcher focused on turning scientific evidence into real-world community health impact. In this newsletter, I share practical insights, thoughtful analysis, and frontline stories that shed light on complex public health challenges—and explore how we can build healthier, more resilient communities together. If you haven’t already, subscribe below for free to stay connected.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on what I have learned, and continue to learn, from real conversations about how we communicate science in our communities.

“Are you one of those experts who ‘believe in science’?”

The question hit me like a splash of cold water. It wasn’t asked with curiosity—it was a test. And one that I initially failed, because my gut reaction was, “Of course I believe in science!”

A community member asked me this question at a rural town hall event about vaccines early in the COVID-19 pandemic. They went on to share deep frustrations with how experts were communicating: talking down to them, not with them, and dismissing them for asking questions. They felt belittled and treated as ignorant for not “believing science.”

On the surface, the question and my response seemed harmless, especially to someone like me, who’s loved the thrill of scientific discovery ever since dissecting a frog in middle school. I assumed they’d appreciate hearing from someone who “believes in science.” But I missed the subtext. I hadn’t fully realized how the way we talk about “believing in science”—and the tone that sometimes accompanies it—can alienate the very people we most need to reach.

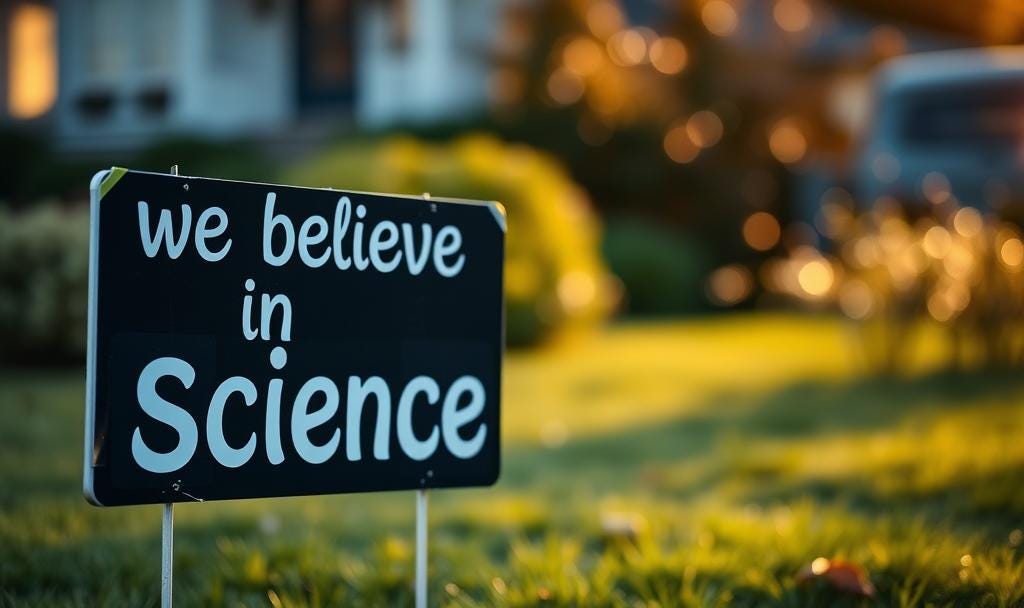

This wasn’t an isolated frustration. On yard signs, social media, and even in my professional circles, I saw the same slogan repeated: “We Believe Science is Real.” Is this well-intentioned? Absolutely. It is meant to show support for evidence, public health, and scientific truth. But after many conversations, I’ve come to understand how often it carries an unspoken addendum: “…and you don't.” Or worse: “…and you’re stupid for not believing.”

It’s no wonder people tune out when approached this way. Instead of inviting people into how science can improve our lives, we draw a line between the “science believers”, assumed to hold the same unquestioned stances on everything from vaccines to the effects of climate change, and the “science deniers,” who don't.

But here’s the irony: science isn’t a religion. It doesn’t require blind faith—it’s a method, a process that evolves through honest questions and relies on evidence to support its claims. And yet, “belief in science” is often treated as a litmus test for belonging rather than an invitation to further understanding.

This dynamic plays out whenever I post, write, or talk about vaccines. I predictably get some who accuse me of poisoning children. But I also get others, often from within the science community, who mock the vaccine-hesitant as “anti-science” and ignorant. This approach is not helpful.

Years ago, I cared for a family hesitant to give their child the MMR vaccine. At every visit for over two years, I would recommend it, and we would talk about their concerns. And then one day they came in and said, “We want to get the MMR shot today.” I was so surprised that I asked them what had changed. It wasn’t new data or a change in the evidence. They said, “Because we trust you and you don’t treat us like we are stupid for asking questions.”

That moment taught me more about science communication than any lecture ever could.

I do believe in science and the good it can bring to the world. I've built my career around studying, applying, and communicating science to improve lives. And I get it: when lives are at stake, it's tempting to dismiss those who are skeptical or don’t seem to “believe in science". But if our ultimate goal is to build trust, creating in-groups and out-groups will always backfire.

And that backfire has real consequences. In just the past five months, deep cuts to scientific research and public health have often been met not with widespread outcry, but with shrugs. Why? In part, because if many Americans have come to see science as arrogant, shaming, and dismissive, why would they rise to defend it? The erosion of trust doesn’t just harm communication; it leaves science vulnerable to those who would rather tear it down than talk.

Affirming people's questions and concerns doesn’t mean abandoning scientific standards—it means earning the right to share them. Our goal should never be to feel superior because we “believe in science” while others don't. Our goal should be to build bridges and show that science, when practiced with integrity and humility, has the potential to help us all live healthier lives.

If we want people to trust science and scientists again, we must start by acting like we trust them. Trust isn't won by declaring facts louder; it's built by listening without judgment. We need to be in communities, meeting people where they are, not where we think they should be. And remembering that science, at its best, doesn't divide people into believers and deniers. It brings people together to solve problems we all share.

Thanks for being part of this community.

-David

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here for FREE to never miss an update and share this with others:

You can also follow me on LinkedIn, Instagram, Substack Notes, and Bluesky.

Community Immunity is a newsletter dedicated to vaccines, policy, and public health, offering clear science and meaningful conversations for health professionals, science communicators, policymakers, and anyone who wants to stay informed. This newsletter is free for everyone, and I want it to be a conversation, not just a broadcast. And if you find this valuable, please help spread the word!

Best substack yet. We need to figure some new slogans that "call people in" instead of calling them out. How about "I believe in children. Science just helps me keep them healthy."

Thanks for reiterating the relational and longitudinal nature of trust. Medicine has become transactional due to big changes in employment, payment models, volume, and documentation requirements. If we want to re-inspire families to vaccinate, we need to sit with them, look them in the eyes, and allow them to share their fears, values, and dreams with us.

While I completely agree with what you’re saying, I fear that society in general has become self-centered and selfish, and propped up by political leaders that just blatantly lie with no shame, repudiation, or consequence, that we are in a time when “truth” and “facts” simply don’t matter to a significant portion of the population, no matter how we communicate that information. I find that to be the most frustrating aspect of all of this, and where I really struggle to see a path forward.